Introduction

Imagine a universe where the Sun suddenly vanishes, leaving us in darkness for a little over 8 minutes – the time it takes for its light to reach us. But today, we’re going to embark on a thought-provoking journey that turns this idea on its head. What if we dared to swap out the Sun for some of the most massive and intriguing objects in the cosmos? In this exploration, we’ll teleport ourselves into the realms of Polaris, Betelgeuse, Sirius, neutron stars, black holes, and even the intriguing world of binary star systems. Together, we’ll uncover the cosmic chaos that would unfold with each extraordinary substitution.

Polaris: The North Star’s Radiant Impact

Our first cosmic heavyweight is none other than Polaris, the North Star, a supergiant that graces our night sky. Its brilliance is awe-inspiring, but what if Polaris replaced our Sun? The sheer intensity of its light would drastically alter the energy reaching Earth. The delicate balance that sustains life on our planet could waver, and the equilibrium that supports ecosystems might be challenged. The scenario brings to light the interconnectedness of our biosphere and the importance of maintaining the conditions that make life possible.

Betelgeuse: A Stellar Dance of Chaos

Now, let’s transport Betelgeuse, a colossal red supergiant, into the Sun’s position. The result? Chaos for our solar system. Betelgeuse’s immense size would extend beyond the orbits of our planets, throwing their carefully orchestrated dance into disarray. The gravitational forces at play would tug and pull on celestial bodies, causing unpredictable shifts in their paths. This celestial ballet reminds us of the intricate interplay of gravity in maintaining the cosmic harmony we often take for granted.

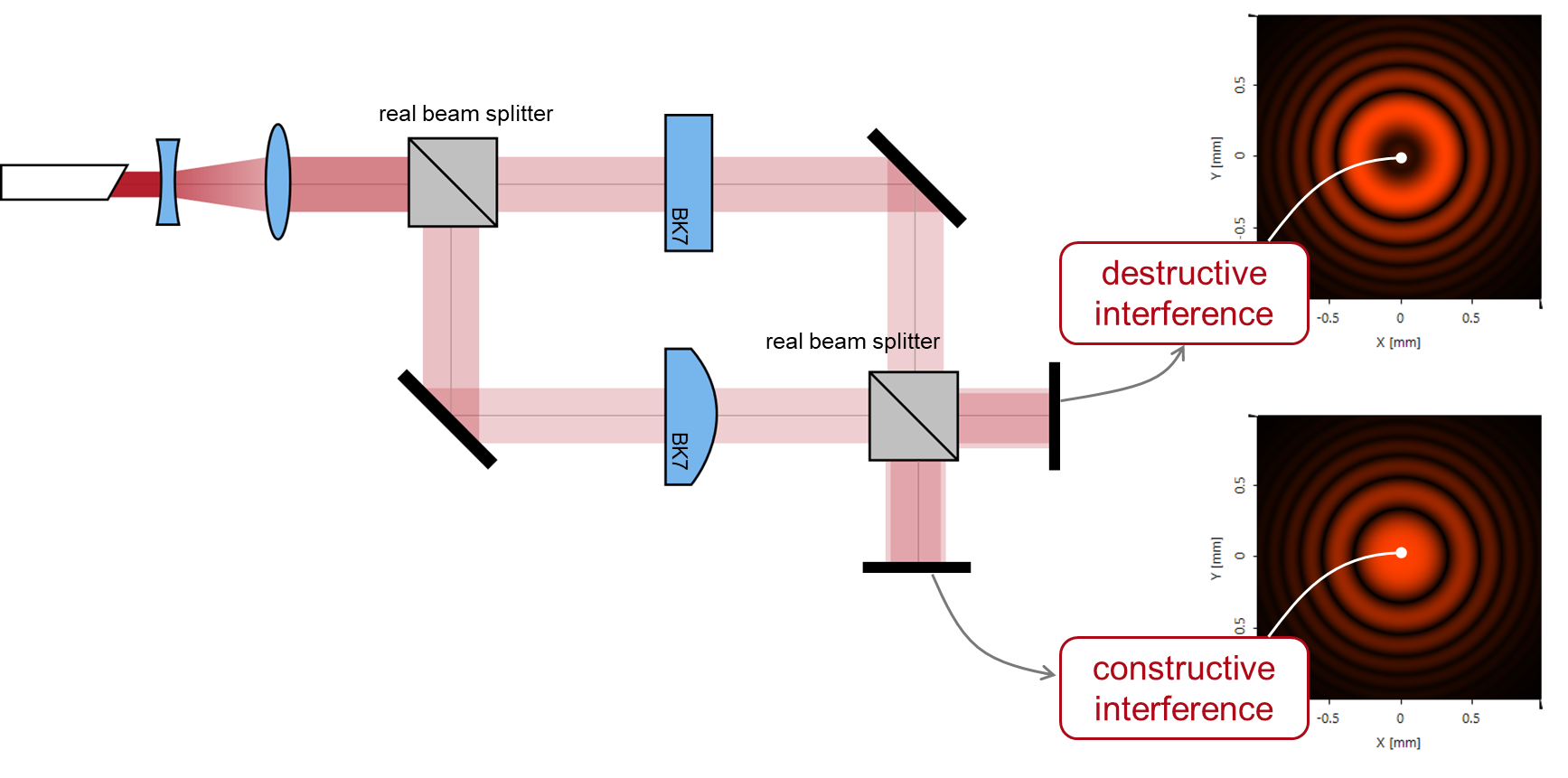

Sirius: A Binary Star System’s Fiery Twist

Imagine substituting our Sun with Sirius, a dazzling binary star system. A binary star system consists of two stars orbiting around a common center of mass. The primary star, Sirius A, outshines our Sun in both heat and brightness. But what if Sirius A became Earth’s new source of energy? The profound impacts on our climate would be unavoidable. The sudden change in energy output could trigger unexpected climate patterns, testing the resilience of Earth’s ecosystems. This scenario prompts us to consider our planet’s adaptability and our capacity to engineer solutions to navigate such celestial surprises.

Neutron Stars: A Gravitational Juggling Act

Enter the enigmatic neutron star, an object of unparalleled density. If we were to replace the Sun with a neutron star, the gravitational juggling act would throw planetary harmony into disarray. The intense radiation and magnetic fields emanating from this dense powerhouse would make Earth’s habitability plummet. It’s a stark reminder of the delicate balance required for life to flourish and the vulnerability of our cosmic neighborhood to radical transformations.

Black Holes: Cosmic Abyss and Mind-Bending Phenomena

The concept of swapping the Sun for a one solar mass black hole opens the door to a realm of bone-chilling cold and warped time perception. The phenomenon of time dilation around a black hole challenges our understanding of reality itself. The tidal forces of a black hole, humorously referred to as “spaghettification,” would stretch and distort objects into oblivion. Moreover, the accretion disk and Hawking radiation introduce us to phenomena that push the boundaries of our comprehension of the cosmos.

Binary Star Systems: A Dance of Tides and Climate Swings

Introducing a binary star system, the most common configuration in the universe, unleashes a cascade of chaos. The gravitational interplay between two stars would send planets’ orbits into a chaotic dance, with some even being flung out of their solar systems. The ever-changing brightness and heat output of binary stars would lead to climate swings and ecosystems adjusting to erratic solar energy. The tides we’re familiar with would transform into wild forces of nature, altering Earth’s rotation, axial tilt, and geological activity.

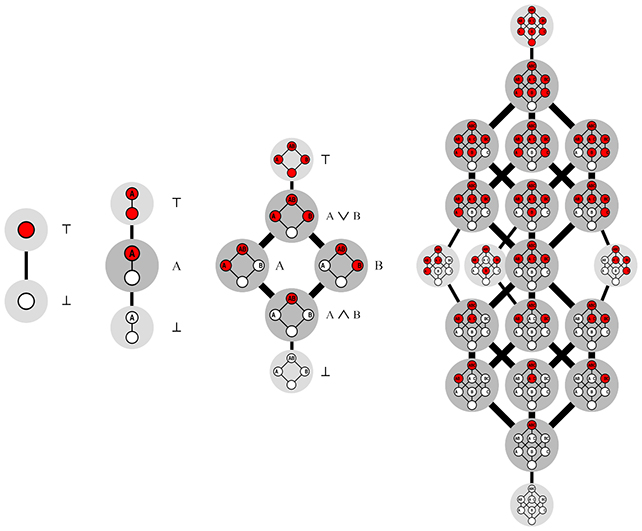

Binary Star Systems: Celestial Duets in the Universe

In the vast cosmic theater, binary star systems take center stage as captivating celestial duets. These mesmerizing arrangements consist of two stars orbiting a common center of mass, engaged in an elegant dance through the cosmos. Comprising the majority of star systems in the universe, binary stars offer unique insights into stellar evolution, gravitational dynamics, and the intricacies of cosmic relationships.

Binary stars come in various flavors. Close binary systems see stars in intimate proximity, often transferring material between them. Wide binary systems boast greater separation, their gravitational interaction more subtle. Spectacular eclipses, where one star passes in front of the other from our viewpoint, provide astronomers with invaluable data on star properties.

These systems play cosmic symphonies, affecting surrounding space and any planets within their gravitational grasp. Planetary orbits may experience erratic shifts due to competing gravitational forces, potentially leading to ejections or collisions. Moreover, the ever-changing brightness of binary stars challenges ecosystems to adapt to alternating light and heat, influencing climate patterns on potential planets.

In binary star systems, the universe’s complexity shines through, revealing how interstellar companions shape the fabric of space, time, and life itself.

Life’s Adaptation to Cosmic Change

As we consider the implications of swapping our Sun for cosmic heavyweights, we’re compelled to ponder life’s adaptability. Evolution on Earth has been shaped by the stable conditions of our Sun. Introducing binary star systems and their radiation, stellar winds, and magnetic fields would redefine the playing field for life’s chances. The potential for cosmic radiation and sweeping winds to influence our planets highlights the delicate balance required for habitability.

Conclusion: Glimpses into Celestial Complexity

Embarking on this imaginative journey of cosmic swaps has unveiled the intricate web of forces and interactions that sustain our universe. From the dazzling brilliance of Polaris to the mind-bending dynamics of black holes and binary star systems, each scenario underscores the fragile equilibrium that enables life to flourish. As we gaze upon the night sky, remember that beyond its beauty lies a tapestry of cosmic complexities that continue to captivate and mystify us. So, the next time you look up at the stars, remember the cosmic chaos that could unfold if the celestial roles were ever reversed.